Supporting progression out of low pay: a call to action

Published 1 July 2021

Note:

As far as has been possible, the Commission has used statistics that apply to the entirety of the UK. When UK-wide data has not been available, the Commission has used statistics either for Great Britain and where possible Northern Ireland or for individual nations of the UK. The scope of the data used is clearly marked within the text.

It should be noted that at times the Commission has chosen to use pre-COVID-19 figures given the uncertainties around the extent of the impact of the pandemic.

Foreword from the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions, The Rt Hon Thérèse Coffey MP

Since my appointment as Secretary of State for Work and Pensions in September 2019, one of my ambitions has been to ensure that everyone, no matter their background, has the opportunity to have a fulfilling working life – one that allows them to rise up the career escalator and to develop throughout life.

Many people already have this opportunity, but for others, especially those in low pay, there can be too many barriers to progression. I want to change this, which is why I asked Baroness Ruby McGregor-Smith, who has also conducted thought-provoking reviews into the barriers facing women and ethnic-minority workers, to lead an independent Commission investigating the challenges faced by those in low pay looking to progress in work.

One of the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic has been the disruption of the labour market in a way not seen for generations. I am proud of the work of my department to ensure that people get the help they need and then to return to the labour market. While that work is still underway through the Plan for Jobs, it is also important that we consider how to put the right systems in place to ensure that once people are in jobs they can continue to learn, develop and increase their earnings.

I thank Baroness McGregor-Smith and her advisory panel for this independent review and I will consider it carefully, as will all of Government, in helping us build back better and fairer.

The Rt Hon Thérèse Coffey MP

Secretary of State for Work and Pensions

Executive Foreword from the In-Work Progression Commissioner, Baroness Ruby McGregor-Smith

I am a passionate advocate for increasing aspiration for all. My own background, and the challenges I and many others have faced, make me so determined to ensure we remove the barriers for everyone. I have experienced the struggles faced by my family trying to make ends meet while I was a child and I know the value of having good opportunities in work to help unlock potential and enable progression.

While this report is aimed at decision-makers, I hope that many people in low pay jobs will read it too. To them, let me be clear, my mum and dad experienced many of the challenges you have faced. I grew up with that and saw how difficult it was at times for them. They managed to break the cycle of low pay and supported my sisters and I to see the value of education and work and I am determined to break the barriers people stuck in low pay face. No individual should be held back and not able to fulfil their potential. I want the United Kingdom to be thought of by everyone as an incredible place to grow up in and for there to be many opportunities in the workplace to progress out of low-paid work.

When I was asked by the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions in early 2020 to lead a review into how people in low pay can be better supported to progress in work, I had no idea of the human and economic catastrophe the country and the world was about to face. While the last year has been incredibly heart-breaking and challenging, it has also given us the opportunity to reconsider how we work. As this report will show, people in low pay find it very hard to progress to, and stay in, higher earning work. This is due to a variety of reasons, including a lack of skills, logistical challenges, such as a lack of suitable transport or childcare arrangements, as well as confidence and motivational barriers.

While there have been reports that have looked at some of these barriers for the low-paid in the past, there have been few, if any, that have brought them all together in one place. This report aims to rectify that. It is not possible to solve the low-paid ‘progression puzzle’ simply by looking at one set of barriers in isolation to the others. No matter how great a training course might be, for example, a person has to believe that they can achieve something by taking that course and they need to be able to actually access the course – is the course run at a time and in a location that works for people who do shifts, for example, or does it offer childcare?

In researching this report, I have had the pleasure of talking to employers, local and devolved authorities, Jobcentre Plus Work Coaches, academics, charities and others. I was guided by an Advisory Panel of innovative and committed organisations who continually supported and challenged me to address the barriers to progression that people in low pay face. I am also grateful for the many organisations that took the time to respond to the Call for Evidence. It is clear that while there is a real passion for supporting people to progress in work, even during the COVID-19 pandemic, many challenges remain.

The Commission has identified a gap in provision for people in low pay. Most Jobcentre Plus support is tailored to help people get in work, as is much of the free or low-cost training provided to help people increase or diversify their skillset. Many employers in low pay sectors also struggle to find the right way to encourage progression among their staff. Simply put, there seems to be a mind-set that progression happens naturally for the vast majority of people. But this is just not the case. In fact, only one in 6[footnote 1] of those workers in low pay ever truly escape.

It is absolutely right that current efforts in the labour market are directed at getting people back into work. However, in doing so, it is imperative that we do not do so in such a way that leaves people in low pay sectors to make their own way afterwards. Nor should we forget about the people who are currently in low-paid work and who may have been in these roles for a considerable length of time. We need to act now if we are to avoid consigning people in low pay to stay there forever.

While I did this report for the Department for Work and Pensions, I am clear that progression cannot be the preserve of one Department or of Government alone. The Departments for Work and Pensions, Education, Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy and Transport, and their equivalents in the Devolved Administrations, collectively have a role to play in ensuring that policies are designed to support progression in work among the low-paid. The Department for Work and Pensions, in particular, has an opportunity to build on its local relationships and to transform its hundreds of Jobcentres into convening centres of expertise on progression support. Employers also need to ensure that they are proactively encouraging and facilitating their employees to develop and progress in work. I am also clear that much of this work will only succeed if it happens at a local level. That is why it is essential that local authorities and other local actors are part of the solution.

This report has recommendations for government at every level and employers. I call on government and employers to consider them carefully and to act now to help support people in low pay to progress in work and to continually keep this work under review. We have an opportunity to transform our approach and to truly help ‘level up’ the country. Let us not waste it. The way forward is clear. The time for reviews is over. It’s time to act.

Baroness Ruby McGregor-Smith

The In-Work Progression Commissioner

Summary

The Commission wants everyone in low pay to have the opportunity and support to progress in work and increase their earnings. The Commission’s report identifies the multiple barriers faced by those in low pay looking to progress and sets out key actions that governments at every level across the UK, employers and others should take to minimise and remove these barriers. It is clear to the Commission that it will require a united effort from these actors to tackle the obstacles that keep people trapped in long-term low pay.

- Chapter 1 is an introductory section which looks at the Commission’s objectives and rationale for focussing on progression out of low pay, considering the evidence to date, including who is more likely to be in low pay. The Commission identifies the multi-pronged nature of barriers to progression and considers findings from the Department for Work and Pensions’ Future Cohort Study and Randomised Control Trial to determine how to best support people in low pay to sustainably increase earnings. The Commission asserts that governments across the UK should seek to play a broad facilitating role, ensuring that there is a long-term focus on in-work progression, including through policy design. The Commission further advocates for greater oversight of and collective action on progression support across UK government departments and their equivalents in the Devolved Administrations

- Chapter 2 considers the role that Jobcentres can play in supporting progression. This role draws on their existing strengths as a national network of local centres of expertise on employment support. Considering the evidence to date on support for in-work progression among the low-paid, the Commission recommends how support that motivates people to progress and gives them the tools to do so could be embedded into the core service of Jobcentres. The Commission also looks at whether the policy design of Universal Credit can better incentivise progression and how well the system in relation to progression incentives is understood by claimants and employers

- Chapter 3 considers how governments and employers across the UK can embed a culture of lifelong learning to support an ambitious and productive workforce. The Commission advocates that developing skills and an understanding of the value of continual learning among the low-paid is essential to help people in low pay sustainably progress in work. The Commission looks at current skills initiatives and identifies the barriers to uptake for those in low pay. The Commission advocates for more bespoke development support for workers in low pay through a progression and learning plan, and describes how to ensure that learning offers are appropriate, accessible and appealing to all demographics of workers in low pay

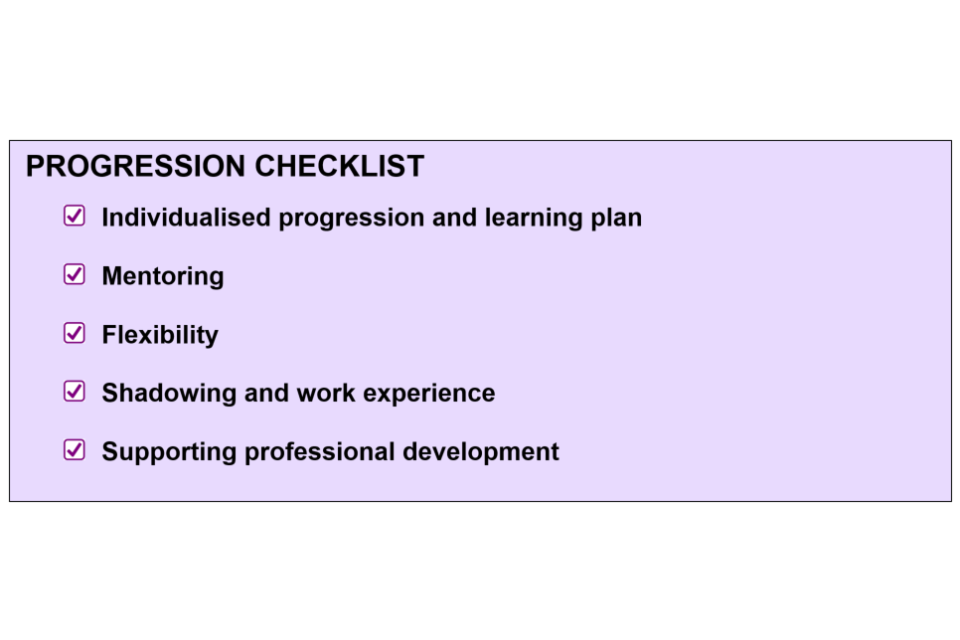

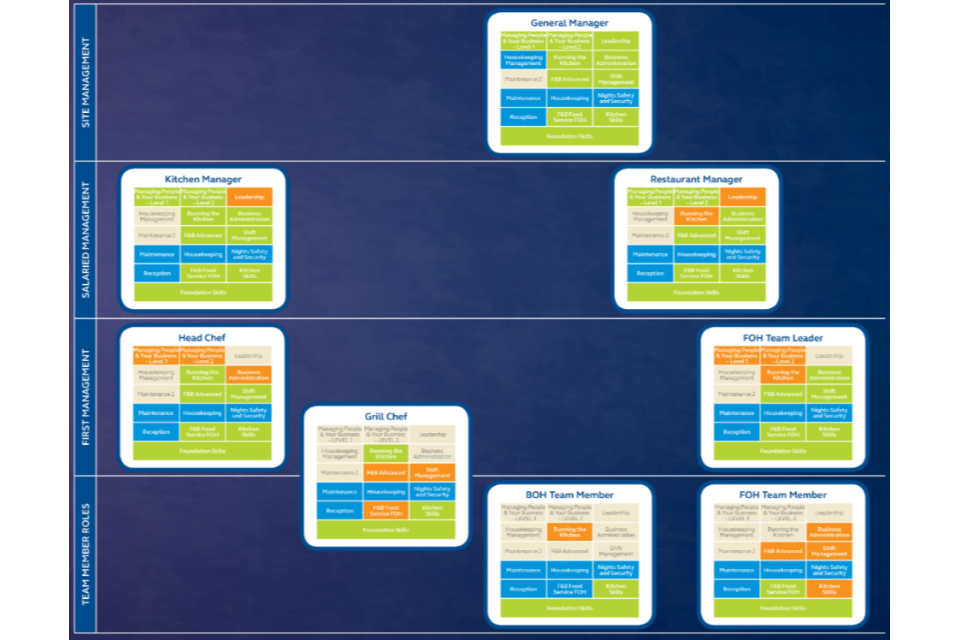

- Chapter 4 explores the role of employers. The Commission advocates that employers are best-placed to engage with their low-paid workers and notes the benefits that progression has for businesses. This chapter sets out actions to assist employers to become ‘progression-focused’ to better support their employees to progress in work and to make the most of their potential. The Commission provides a 5-point progression checklist, which employers of all sizes can adopt, and also makes recommendations on how employers can embed progression into their organisational culture. The Commission also argues for transparent national and local progression pathways for each low pay sector, to help workers have a clear ‘line-of-sight’ to their potential career path

- Chapter 5 looks at the potential that public procurement has in incentivising good employment practice, including progression. The Commission looks at case studies of programmes which go over and above their core contract commitments to deliver social good as part of public sector spending. The Commission encourages government to go further and increase the minimum weighting of social value in public procurement to 20% over time as well as developing mechanisms for sharing good practice in assessing social value between public procurement teams in local, national and devolved authorities

- Chapter 6 focuses on the significant barriers that lack of suitable transport and childcare pose. The Commission argues that local bus networks offer an opportunity to transform employment potential for workers in low pay sectors and recommends governments throughout the UK continue to enhance reliability and availability of services and decrease costs to help those in low pay seeking to progress. In relation to childcare, the Commission looks at the flexibility, availability and understanding of current provision, concluding that governments across the UK must be more aware of the role childcare plays in supporting progression and act accordingly. The Commission also makes recommendations to employers in relation to childcare and transport for their workers

Chapter 1: Introduction

The Commission’s objectives

The Department for Work and Pensions set up the In-Work Progression Commission in March 2020 to look at the barriers to progression for those in low pay roles, particularly for those with whom the Department comes into contact through its Jobcentres. This was just weeks before the first public health lockdown of 2020 and the Commission’s work since then has had to balance short-term considerations of unemployment with longer-term considerations of what more could be done to support those in low pay. The Commission is extremely grateful to its partners throughout the UK, both within and outside government, who worked with it through this period and provided valuable time and insight which has been instrumental in shaping the report and recommendations.

It has been clear through the course of the Commission’s work that the barriers to progressing out of long-term low pay, and most of the accompanying solutions, are relevant to all those in low pay, even if they do not interact with the welfare system. The Commission therefore decided to include not only issues relating to the Department for Work and Pensions’ direct service delivery, but also wider issues of policy and culture driven by government and employers, which enable or unintentionally impede progression out of low pay.

Defining progression and the Commission’s focus on progression out of low pay

The Commission learned that there is no single, widely recognised definition of in-work progression. Studies commissioned by the Department for Work and Pensions, which are discussed more fully later in this report, suggest that views of progression are varied. For some it is about increasing hours, while for others it is primarily about increasing hourly pay. The Commission also recognises that being in work is a pre-requisite to progression and so, for some, addressing the short term instability of insecure, low-hours or seasonal contracts, or the longer term concern of sectoral decline, will be a crucial element of any approach to in-work progression. The 2017 Taylor Review of Modern Working practices reflected these varied perspectives when it chose to assess quality work according to 6 criteria: wages, employment quality, education and training, working conditions, work-life balance, and consultative participation and collective representation[footnote 2]. The Commission supports this helpful work and that of the UK government’s response, the Good Work Plan[footnote 3]. The focus of this Commission’s report, however, is how to enable higher hourly wages for better quality work, whether for the same employer, in the same field, or in a different sector entirely. In this report, the Commission identifies the main barriers to progression out of low pay and sets out the key actions that the Commission believes need to be taken to support those stuck in low pay to progress in a meaningful and sustained way.

It is clear to the Commission that both employers and governments at every level have central roles to play in tackling the obstacles that keep people trapped in long-term low pay. Employers are best-placed to engage with their low-paid workers, understand the challenges they face when seeking to progress and consider what action they can take to make the most of the potential of their employees. The report also sets out steps that governments, at national and local level, can take to ensure policies are designed to help those in low pay progress. This includes playing a broad facilitating role, whether through incentivising employers to act by embedding consideration of progression into public procurement processes, actively encouraging lifelong learning for all or ensuring this country has the right infrastructure to support an ambitious and productive workforce.

Low pay in the UK

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) defines low pay as less than two-thirds of median hourly earnings. In 2019, in Great Britain, the median hourly wage was £13.34, therefore, according to the ONS definition, low-paid workers were earning an hourly wage of £8.89 or less[footnote 4]. In April 2019, there were over 4.2 million low-paid jobs in Great Britain by this definition, 16% of all jobs[footnote 5]. Furthermore, research from the Resolution Foundation for the Social Mobility Commission found that only one in 6 of those low-paid in 2006 managed to escape low pay over the course of the following decade[footnote 6][footnote 7].

Low pay is not evenly spread. Low-paid roles are more prevalent in particular sectors and geographical areas and the likelihood of being in low pay also varies for different demographic groups.

Location

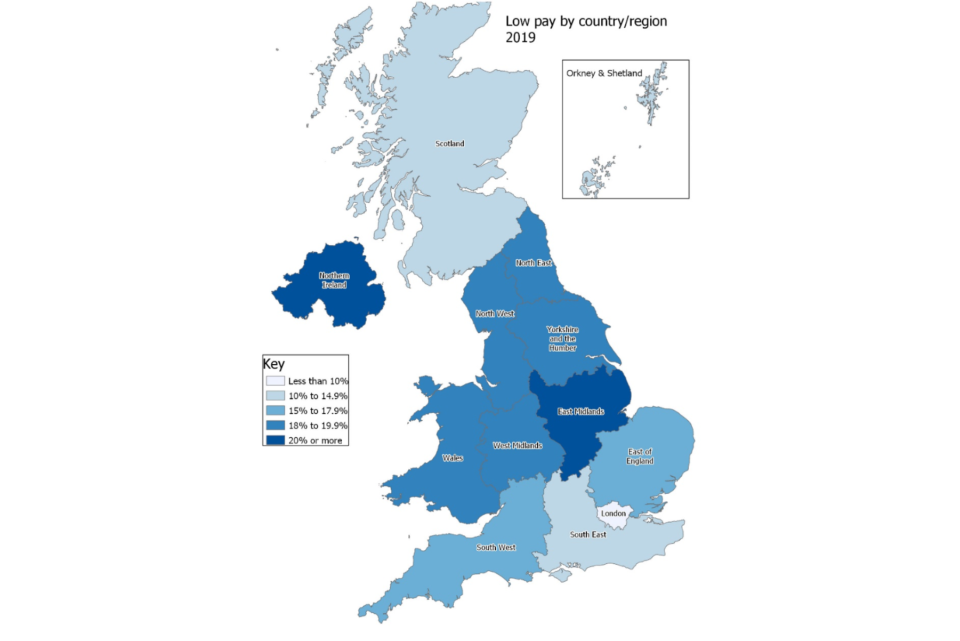

Within the UK, in 2019, Northern Ireland (21.1%), the East Midlands (20.1%), the North East (19.9%) and Yorkshire (19.6%) had the highest proportions of low-paid jobs. London (8.7%), the South East (13.9%) and Scotland (14.5%) had the lowest proportions of low-paid jobs. In Wales, 19.1% of jobs were classed as being low-paid[footnote 8].

Figure 1 Data taken from ONS, Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings

However, inequalities are often more striking when looking within UK regions and constituent nations – comparing their constituent counties and local authority areas – than when making comparisons between regions. Unlike many other countries, where inequality in productivity and pay often reflects an urban-rural divide, the distribution of low pay is mixed in the UK. While some large cities do well, others do not. Some small towns and rural areas do comparatively better than poorer performing cities[footnote 9].

Improving progression out of low pay can therefore play an important role in levelling up opportunity and growth within regions, as well as across the UK.

Sectors

In April 2019, as shown in figure 2, close to half of all low-paid jobs (45%) in Great Britain were in the Wholesale and Retail trades and Hospitality. Residential and Social Care and Business Support Services (which includes outsourced agency work) are also sectors with large numbers of employees in low pay, together accounting for 21% of low-paid jobs[footnote 10].

Figure 2 Data taken from Office for National Statistics. (2019) Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings. In-house analysis

Numbers of employee jobs in thousands in Great Britain:

| Industry | Low-paid jobs | Better-paid jobs | All jobs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wholesale and Retail | 1,083 | 2,565 | 3,648 |

| Hospitality | 812 | 669 | 1,481 |

| Business Support | 449 | 1,212 | 1,661 |

| Education | 309 | 3,346 | 3,655 |

| Residential and Social Care | 449 | 931 | 1,380 |

| Manufacturing | 250 | 2,097 | 2,347 |

| Creative and Sports | 158 | 392 | 550 |

| Rest of Economy | 703 | 10,396 | 11,099 |

| Total | 4,213 | 21,607 | 25,821 |

Source: ASHE, 2019, GB

Demography

The Commission has also learned that certain worker groups are more likely to be in low pay. 62% of low-paid jobs in Great Britain in 2019 were held by women, according to the ONS Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (2019)[footnote 11][footnote 12], compared to 51.1% of all employee jobs being held by women in 2019[footnote 13]. Women are more likely to be in low-paid jobs than men across almost every sector. The only low-paid sector where women make up fewer than half of low-paid workers is Manufacturing, where 44% of low-paid jobs are held by women. Women in Wholesale and Retail, Hospitality and Residential and Social Care make up 35% of all low-paid employee jobs.

Figure 3 Data taken from Office for National Statistics. (2019) Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings. In-house analysis

The majority of low paid jobs are held by women in almost every sector

| All low paid jobs, millions | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Education 0.31 | 87% |

| Residential and Social Care 0.45 | 84% |

| Total 4.21 | 62% |

| Other 0.70 | 60% |

| Wholesale and Retail 1.08 | 59% |

| Hospitality 0.81 | 58% |

| Creative and Sport 0.16 | 57% |

| Business Support 0.45 | 53% |

| Manufacturing 0.25 | 44% |

In 2019, 30% of all low-paid employee jobs in Great Britain were held by young people, while 27% were held by older people[footnote 14]. In comparison, 10.9% of all employee jobs in Great Britain were held by young people in the same year, while 30.6% were held by older people[footnote 15].

Figure 4 Data taken from Office for National Statistics. (2019) Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings. In-house analysis[footnote 16]

Low-paid jobs held by different age groups in each sector as a share of all low-paid employee jobs

| Sector | Older (50+) | Middle-aged | Young (aged 24 and below) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wholesale and Retail | 7.5% | 10.3% | 7.9% | |

| Hospitality | 2.9% | 7.5% | 8.9% | |

| Other | 4.8% | 7.4% | 4.5% | |

| Business Support | 3.0% | 5.4% | 2.2% | |

| Residential and Social Care | 3.5% | 5.1% | 2.0% | |

| Education | 2.6% | 3.4% | 1.3% | |

| Manufacturing | 1.9% | 2.8% | 1.2% | |

| Creative and Sport | 0.7% | 1.2% | 1.8% |

The Commission also received a significant number of representations through its Call for Evidence that asserted that ethnic minority and disabled workers also face significant challenges around progression and are more likely to be stuck in low pay for long periods of time. While the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings does not provide statistics for the proportion of low-paid jobs which are held by ethnic minority or disabled workers, data regarding pay gaps and occupation types provides an indirect indication of the challenges these groups face in relation to progression.

In 2019, the ethnicity pay gap between White and Ethnic Minority groups stood at 2.3% in England and Wales, its lowest level since 2012[footnote 17]. However, this headline figure masks a wide variation in the experiences of different ethnic minority groups. For example, in 2019, in England and Wales, the median hourly pay for the Bangladeshi ethnic group was £10.58, while for the Pakistani ethnic group it was £10.55 per hour, compared with £12.49 per hour for White British employees[footnote 18]. In contrast, individuals from the Chinese, White Irish, White and Asian, and Indian ethnic groups earned higher median hourly pay than White British employees across 2012 to 2019[footnote 19].

Furthermore, in the UK in 2018, 11% of people from the White ethnic group worked under the ‘Managers, Directors and Senior Officials’ occupation group, compared to 5% from the Black ethnic group[footnote 20]. In the same year, 41% of workers from the combined Pakistani and Bangladeshi ethnic group were in the three least skilled types of occupation compared to 24% of White British workers.

For disabled workers, in 2018, the pay gap in the UK was 12.2% although around a quarter of the difference in mean pay can be accounted for by factors such as qualification and occupation[footnote 21]. Disabled workers are also less likely than non-disabled people to move into work, as well as being more likely to move out of work[footnote 22]. In 2018, disabled employees in the UK were generally under-represented in higher skilled and typically higher paying occupation groups, while they were over-represented in lower skilled and lower paying occupations when compared to their non-disabled counterparts[footnote 23].

Progression out of low pay

Resolution Foundation analysis, which tracked initially low-paid employees (earning below two-thirds of median hourly pay in 2006) over the course of a decade, found that under 25s were less likely to get stuck[footnote 24] in low pay than the average low-paid employee[footnote 25]. A proportion of this age group will escape low pay over time by moving from an occupation that pays relatively low wages into an occupation with higher average earnings.

For those in their late thirties onward, progression out of low pay is proving difficult. Older individuals who were low-paid in 2006 were less likely to have escaped[footnote 26] low pay in 2016 than 16 to 20 year olds[footnote 27]. Those in their late thirties in 2006 were already 33 percentage points less likely to progress than a 16 to 20-year-old, with the size of the gap increasing for older groups.

In addition to age, gender also has an impact on progression out of low pay, with women more likely to remain in low-paid work for longer[footnote 28]. Women are also more likely to spend more time in part-time work, a factor which is negatively linked to progression.

The impact of COVID-19

The Commission appreciates that its findings and recommendations will need to be considered alongside the overall economic recovery effort to address the impact of COVID-19. The costs of the pandemic have particularly impacted some sectors, with some, such as hospitality, suffering a 90% fall in output during the first lockdown, while others, such as finance, have hardly been affected[footnote 29]. While it is right to focus now on helping the economy to recover and supporting people back into employment, it is also important to put the right structures in place to support people to progress and move into better quality work as the economy strengthens.

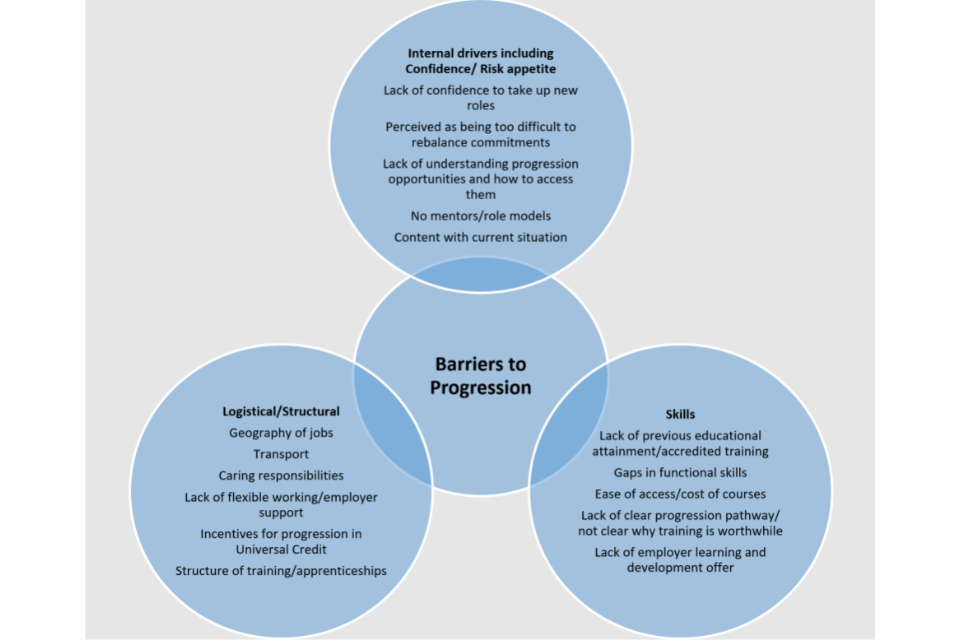

Barriers to progression

For many workers, the barriers to progression are multi-pronged, overlapping and change over time. The barriers can be broadly divided into three categories:

- logistical and structural

- skills

- internal drivers including confidence/risk appetite

Figure 5 Diagram created by the Commission

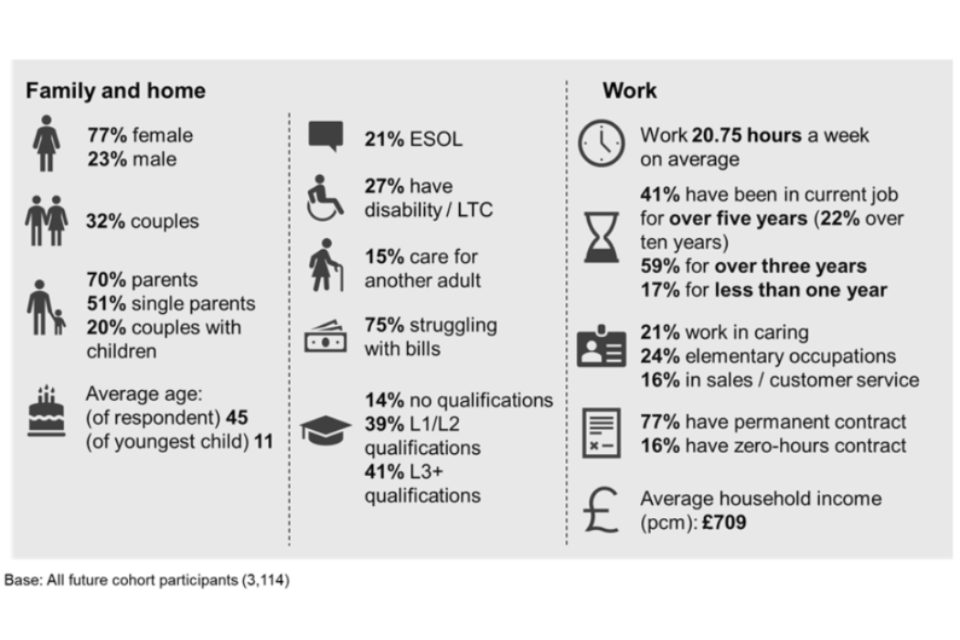

In 2019, the Department for Work and Pensions commissioned Ipsos MORI to produce the Future Cohort Survey[footnote 30]. The survey looked at barriers to progression for the ‘future cohort’: individuals in Scotland, England and Wales who were working and receiving tax credits or Housing Benefit only, who, based on their earnings, might move into the ‘Light Touch’ conditionality group if they moved onto Universal Credit.

Overall key characteristics of the future cohort

Figure 6 Data taken from The Department for Work and Pensions. (2021) The Future Cohort Study: Understanding Universal Credit’s future in-work group

Many of the future cohort are in stable employment. For example, 4 in 10 (41%) have been in their current job for over 5 years, and a similar proportion (42%) have been in their role for between one and 5 years. Respondents with no qualifications are more likely to have been in the same job for more than 5 years (48%).

Many work short hours and face financial difficulties. On average they work 21 hours per week. Average household earned income is £709 per month, while a quarter (26%) have monthly earnings of less than £500 and 16% more than £1,000. Three-quarters (75%) of the future cohort report at least some difficulty with keeping up with their bills and other financial commitments. Parents are more likely to report financial difficulties than single adults (77% compared with 71%).

Reflecting the stable work that many are in, the majority of the future cohort are satisfied with the work that they do. Eight in 10 (81%) report feeling satisfied with their job overall. Satisfaction is highest with work-life balance (80%) and the number of hours worked (79%). Two-thirds are satisfied with their pay and training opportunities (64% and 66% respectively) and over half (56%) with opportunities for career development. Reflecting the high overall satisfaction, two-thirds (64%) of respondents strongly agree that their biggest priority is keeping their current job rather than looking to progress at work.

While most of the future cohort are satisfied with their current job, many are also taking steps to explore or pave the way for progression. Around 7 in 10 (72%) report taking at least one action to progress in the past 12 months, most commonly taking a training course (34%) or speaking to their manager about progression opportunities (32%). However, nearly half (47%) feel they first need to improve their skills and qualifications, with IT skills an area in which many felt at a disadvantage.

In addition to these findings, the Commission learned through its consultations and Call for Evidence[footnote 31] that many are also unconvinced of the personal benefits of progression, especially if it means unpicking carefully balanced work-life arrangements for uncertain benefits. The Equality and Human Rights Commission has found that workers frequently lack the necessary information needed to consider potential personal progression as too few low pay sectors and businesses set out clear progression pathways[footnote 32]. Furthermore, the Commission has heard that the lack of flexibility in more senior roles can often mean that women in particular are unable to take up opportunities to progress due to the need to work around existing caring responsibilities and challenges associated with accessing affordable childcare at the required hours[footnote 33].

What would support progression?

Turning to the support that people felt they needed to progress at work, a randomised control trial (RCT) run by the Department for Work and Pensions[footnote 34] considered how those on Universal Credit could be supported to increase their earnings and progress in work. It found that about a third of the cohort looked to their employers for support, whilst a quarter wanted more support from their local Jobcentre. Those who had benefited from talking to their Work Coach felt that their Work Coach had tailored the support to their needs and that this had increased their motivation.

The Future Cohort Study sample appeared more willing to seek support. Most (6 in 10) would look to their employers for support while around a third would consider seeking support from their Jobcentre. People’s needs varied. While many valued a job that would fit around their caring and family responsibilities or health condition, some were looking to increase their earnings and expressed a wish to come off benefits or tax credits. A common theme in both studies was the value people attached to having personal support which felt tailored to their needs.

In terms of skills, job-related training appeared to be effective in raising earnings for the RCT cohort. Among Future Cohort Study participants, over half wanted support to improve their work-related skills, and many identified support to enter further or higher education (45%) or find a new job (42%) as being useful to progression.

The Commission has also heard about Universal Credit and its impact on progression out of low pay. While it was largely recognised by respondents to the Call for Evidence that Universal Credit is an improvement on the benefits it replaces, the Commission heard that claimants and their employers find the structure of Universal Credit confusing and often misunderstand the implications that an increase in working hours will have for their award. It can also act as a disincentive to progression because pay increases when moving from entry-level to first-line supervisory roles in low pay sectors can be very small and workers do not believe that there is sufficient reward for taking on greater hours and undoing stable and trusted childcare and transport arrangements.

Recommendations

It is clear that the barriers to progression are multi-faceted and interlocking and cut across the responsibility of a number of central government departments, including in particular the Department for Work and Pensions, the Department for Education, the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy and the Department for Transport. Therefore, substantially increasing progression out of low pay requires cross-government effort.

1.1. For national and England-only policies, the UK government should create a body or oversight mechanism that can bring together the work of the Department for Work and Pensions, the Department for Education, the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy and the Department for Transport in providing a long-term focus on in-work progression. The Devolved Administrations should consider doing likewise for relevant policy areas.

Chapter 2: The Low-Paid on Universal Credit: The Department for Work and Pension’s Role in Progression

Universal Credit was introduced in 2013, replacing a range of existing benefits and tax credits. This brought the Department for Work and Pensions into contact with more people who are in work and on low pay, while previously its focus was primarily on those out of work. There are currently over 2 million people on Universal Credit who work, which is close to 2 in 5 of all claimants[footnote 35]. This means that the Department has at least some contact with over 2 million people in low pay. The Department runs over 600 Jobcentres across Great Britain, forming an important network of frontline support for unemployed people with, crucially, the potential to extend this support to working people on low pay.

It was surprising for the Commission to note that Jobcentres do not currently have an in-work progression support offer. Currently, Jobcentres are understandably focused on mitigating the impact of COVID-19 by helping get people back into work. However, beyond COVID-19, there are 2 things the Department must do to help those on low pay through its Jobcentres: make progression support part of its core service; and make sure that the financial incentives built into the Universal Credit system are conducive to progression and well-understood by claimants.

This chapter is split accordingly – first it looks at a new role for Jobcentres as conveners or co-conveners of local knowledge and expertise on jobs, skills and progression pathways; and secondly, at the design of Universal Credit and its financial incentives for progression.

A new role for Jobcentres

Jobcentres have a range of existing strengths which provide a strong foundation on which to build in-work progression support: a national network of Jobcentres staffed by a large workforce of Work Coaches with knowledge of the benefit system, local labour markets, childcare, and skills; a recognised brand; relationships with national and local employers, and local authorities; and emerging capabilities to interact with claimants virtually.

Even so, introducing in-work progression support requires a major shift in how Jobcentres operate. The challenge associated with doing so was articulated by the Work and Pensions Select Committee in 2016:

For in-work progression to succeed, Jobcentre Plus (JCP) Work Coaches will need to be a new kind of public servant, possessing new skills and operating on a new agenda. They will need to address structural barriers to progression, such as access to childcare, skills development and job opportunities, on a personalised basis. They will also need to understand local labour markets and engage with employers to a far greater extent than they have done before. Compared to the existing role of moving people out of work into employment, this will require the [Department for Work and Pensions] to nurture Work Coaches with a substantially expanded set of skills.[footnote 36]

The Work and Pensions Select Committee

Through its Call for Evidence, the Commission heard a similar call for Jobcentres to evolve into hubs of expertise on skills and progression. Responses suggested that individuals need more specialised support to progress, better relationships with Work Coaches and, critically, they need to view Jobcentres as welcoming, inclusive and sensitive to personal circumstances.

Jobcentres have an important role to play in delivering in-work progression at a local level. There is more that can be done by Jobcentres to co-ordinate engagement between employment support providers, local authorities and employers to help more jobseekers to find and sustain employment. Jobcentres taking on a greater leadership role, as a hub for employability, by sharing more data about labour market challenges so that providers of employment support schemes, in partnership with local authorities and employers, can best support disadvantaged communities. A data driven approach to helping people into employment is the best way to target resources.

Seetec, In-Work Progression Commission’s Call for Evidence[footnote 37]

… they [Jobcentres] should look to expand into the concept of Employment and Training Hubs….the hubs should focus on adult learners, post-19, complementing recent Government investment in younger learners, and should provide:

- a one-stop training and employment matching service

- rapid diagnosis of adults’ skills and development needs

- emergency support for upskilling back into meaningful employment via short courses specifically designed to get people into jobs

- continuing access to training and upskilling for those most at risk of displacement from their current roles, by factors such as automation and AI

- ongoing training focused on improving business productivity

In areas where they are located, they would seek to reflect local and regional needs, and improve the visibility of and access to existing training provision through partnerships with employers, training providers and local government. They will make today’s sometimes fragmented skills training system more coherent and intelligible to adults seeking employment, and to existing and potential employers in each region where they are established.

City and Guilds, In-Work Progression Commission’s Call for Evidence[footnote 38]

The Commission is aware of the Department for Work and Pensions’ Youth Offer. This mostly supports Universal Credit claimants aged 18-24 who are not in work and are in the intensive work search regime. As part of this, the Department is opening new Youth Hubs in England, Scotland and Wales. They are co-delivered and co-located with partner organisations to provide access to multiple services and work related opportunities in one place. Some will offer a drop-in service for young people who need support to find or progress at work, including those not claiming Universal Credit. The Commission is supportive of Youth Hubs and hopes they will help young people to progress at work.

The evidence to date on in-work progression

There is already some evidence of what could make Jobcentre support for in-work progression most effective.

In-Work Progression Randomised Control Trial

As mentioned in the previous chapter, between 2015 and 2018, the Department undertook a large Randomised Control Trial (RCT) that tested the impact of adopting a similar approach for in-work claimants as is used for unemployed claimants[footnote 39]. The trial focused on testing increased contact with a Work Coach and a requirement to fulfil a ‘claimant commitment’, with benefits reduced if the claimant did not participate.

Those selected for the trial were randomly assigned to one of three levels of support: fortnightly contact with a Work Coach; contact every 8 weeks; and, as a baseline offer, an initial telephone call, followed by a call after 8 weeks. Thereafter claimant earnings were monitored to compare how each group fared on average.

Figure 7 Source: Universal Credit: In-Work Progression Randomised Controlled Trial, Impact Assessment

| Amount of in-work support | Average increase in earnings per week at 52 weeks | Increase in average earnings, compared to the baseline group |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline group – 2 telephone calls with a Work Coach | £5.20 | .. |

| Contact with Work Coach every 8-weeks | £9.63 | £4.43 |

| Fortnightly contact with Work Coach | £10.44 | £5.25 |

The results of the trial were published in September 2018. The analysis compared how people had got on 52 weeks after joining the trial, by comparing the average earnings of each group. The fortnightly group were, on average, earning £5.25 per week more than the baseline group, whereas the eight-week contact group were earning an additional £4.43 per week. Each level of intervention was ‘value for money’, generating higher earnings that exceeded the cost of providing the support, although the eight-week contact had a clear lead by this criterion. A follow-up study at 78 weeks concluded that the positive impact on progression had been sustained for the fortnightly group, but not the 8-week contact group[footnote 40].

Overall, the trial found that the lowest earning claimants appear to benefit from having regular contact with a Work Coach, albeit that the magnitude of the earnings lift appears to be quite modest. A survey that accompanied the trial highlighted the importance of the interaction between an individual’s personal motivation and their relationship with their Work Coach. Those with greater barriers to overcome often increased their hours and earnings when given one-to-one support.

The Employment Retention and Advancement demonstration

The Employment Retention and Advancement (ERA) demonstration (2003 to 2007)[footnote 41], targeted lone parents who were either unemployed or were receiving Working Tax Credits, and the long-term unemployed. It offered individuals financial incentives for completing training and for sustaining full-time work. Coaching and support were provided, together with a fund to help with out-of-pocket expenses. The ERA found that people responded to the financial incentives for completing training. The trial showed people were more likely to take courses relevant to their occupation, with those with lower educational qualifications and parents of older children most likely to do so. Yet, the link between course-taking and higher subsequent earnings was not straightforward, with more course-taking not by itself enough to foster earnings progression. The ERA also found that the longer-term outcomes differed between the lone parents and the long-term unemployed. After three years, the (previously) long-term unemployed had sustained their higher earnings impact, but the lone parent groups largely had not, once the financial incentives were withdrawn.

A future in-work progression offer

Ideally, the Commission would want in-work progression support to be fully mainstreamed into the work of Jobcentres. Everyone should be given the opportunity of support to progress and this support should be provided over a sustained period of time. This means that if you are in receipt of Universal Credit and in contact with a Jobcentre, you should be spoken to about progression regularly. The Commission recognises that there is not enough detailed evidence on what works best in supporting in-work claimants to move into higher-paid work and that the Department for Work and Pensions is likely to want to trial different approaches. The Commission believes that one approach could be to provide an annual progression-related career conversation which would:

- signpost claimants towards high-quality training

- support claimants to take calculated risks (such as travelling a distance for a job interview in an industry different to the one they are in currently)

- share local knowledge about employers and employer needs, through bespoke individual progression and learning pathways

Recommendation 2.1: Jobcentres need to have an established, credible in-work offer for all working benefit claimants. This could include, for example, annual, high quality, progression-focused career conversations. To realise this, Jobcentres need to invest in specialist expertise in progression. This will include acting as a specialist hub for expertise on local labour markets in close partnership with local actors including employers, local authorities and skills providers, amongst others.

The Commission understands the sensitivities around sanctions and would like, instead, to propose a system of incentives for these progression conversations. For every milestone that a claimant reaches on their individual progression and learning pathway, they could, for example, be ‘awarded’ with credits which they can put towards training, or certification costs, or childcare or transport costs to allow them to reach their next milestone.

Recommendation 2.2: The Department for Work and Pensions should consider ways to incentivise claimants to reach milestones on their individual progression and learning pathways. For example, for every milestone that a claimant reaches on their individual progression and learning pathway, they could be ‘awarded’ with credits which they can put towards training or certification costs, or childcare or transport costs to allow them to reach their next milestone.

The Commission is conscious that mainstreaming a quality progression offer into the work of Jobcentres will require more of Work Coaches. Work Coaches need to know what progression means for different types of workers and what progression journeys look like locally in different sectors. This understanding would need to be rooted in strong local partnerships and sectoral knowledge.

To support Work Coaches in developing this knowledge, or perhaps as an alternative solution, the Commission believes there may be a need for a more senior progression specialist team to support each Jobcentre or a district of Jobcentres. The purpose of these specialist teams would be to: develop knowledge and expertise on progression in their local area; form strong local partnerships, especially with local authorities and employers; identify and source training providers; liaise with sector bodies; and pass this knowledge on to Work Coaches on a regular basis and on request as required. The benefits of this arrangement, should it be successful, would be immense. It could even mean that Jobcentres, in partnership with local authorities, become convening bodies on the issue of progression, committed to shaping the progression landscape on a local level. In designing this arrangement, the Commission encourages the Department for Work and Pensions to work closely with the Department for Education and the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy in particular.

This uplift in expertise available to Jobcentres may also go some way in addressing concerns raised in the Call for Evidence about a lack of confidence in the ability of Jobcentre staff to provide encouraging, personalised and enabling support to claimants, while also balancing enforcement duties.

…. working clients struggle to engage with Jobcentres, either because they feel it is unsuitable or overly-associate it with unemployment support.

Better Placed, In-Work Progression Commission’s Call for Evidence[footnote 42]

We advocate a shift to a more supportive and enabling approach. Support needs to be genuinely tailored to individual needs, and advice should be informed by broader economic and industrial strategies.

Kumar and Jones, Manchester Metropolitan University, In-Work Progression Commission’s Call for Evidence[footnote 43]

The Randomised Control Trial demonstrates that the Work Coach-claimant relationship is absolutely crucial. There are several ways to enhance the experience of claimants in working with the Department’s frontline staff. As described above, this includes building greater staff expertise on progression, including local and regional industrial landscapes and strategies, alongside broader knowledge of the Department’s vision and aims for progression. It might also be a case of reassessing Jobcentre staff caseloads. Adjusting the design of Universal Credit itself, as set out below, may also contribute to a changed perception of Jobcentre staff by claimants.

Progression incentives in Universal Credit

Universal Credit represents a major reform of the welfare system. It replaces 6 benefits: income-based Jobseeker’s Allowance, income-related Employment and Support Allowance, Income Support, Housing Benefit, Working Tax Credit and Child Tax Credit. These benefits were provided by the Department for Work and Pensions, Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs and local authorities. This simplification of financial support has removed the disruptive barriers which previously arose when people started work and had to cease claiming certain benefits and apply for different benefits.

Universal Credit is intended to strengthen incentives to enter any form of paid work and, amongst those who are already in work, to increase hours or earnings. It is designed to remove barriers to temporary, flexible and part-time work, while also ensuring claimants are better off in work. In this way, Universal Credit targets resources towards reducing the number of workless households, by increasing the incentive for at least one member of the household to enter work.

Financial incentives in Universal Credit

The current policy design of Universal Credit includes a work allowance which is the amount some households can earn before their award starts to reduce. Work allowances are intended to encourage those members of households with children and/or an adult with a disability or health condition which affects their capability for work to enter work. There are 2 levels of work allowance: a higher work allowance of £515 a month for those without housing costs included in their Universal Credit award; and a lower work allowance of £293 a month for those with housing costs included.

After any work allowance is taken into account, Universal Credit reduces as household earnings increase according to a single taper rate of 63% which applies to all households with earnings. This means that for every pound the household earns above any work allowance, the Universal Credit award is reduced by 63p.

The Commission has heard from academics, employers, local authorities, trade unions and others about the challenges of designing a benefit system that provides a strong safety net for people in real need, while also ensuring that, that safety net is not withdrawn too quickly as individuals start to get back in to work. The Universal Credit approach of benefit reducing gradually and at a consistent rate as earnings increase has the merit of avoiding the cliff edges of the previous arrangements. Broadly, returns to the Commission’s Call for Evidence on this topic agreed that Universal Credit is an improvement on the benefits it replaces in terms of support for people in work.

In line with the fundamental policy design of Universal Credit as a household benefit, work allowances are applied to a Universal Credit claim rather than to individual claimants and earnings are aggregated for the Universal Credit calculation. The work allowance applies to the household’s earnings rather than individual earnings. Because of this, work allowances are a stronger work incentive to a first rather than a second earner, where any additional earnings above the work allowance level are immediately subject to the 63% taper. The Institute for Policy Research, University of Bath, shared findings from their research which suggested that some claimants found the 63% taper rate ‘demotivating’[footnote 44]. Employers have echoed this in discussions with the Commission[footnote 45].

Responses to the Call for Evidence also pointed to the likelihood that the taper rate affected women’s work incentives more than men’s, due to women often being the second earner. The Institute for Policy Research, University of Bath highlighted their findings that as support for the cost of childcare is also absorbed within the monthly payment and tapered away as earnings rise, some working households were unable to pay their childcare fees and got into debt as a result[footnote 46]. It would be understandable if claimants in this position decided that any benefits associated with promotion or increased hours were outweighed by financially unsustainable impacts.

The Commission recognises that the Department for Work and Pensions has made improvements to the financial incentives in Universal Credit, reducing the taper rate from 65% to the current rate of 63% in April 2017 and significantly increasing work allowances by £1,000 a year in April 2019, which undoubtedly provided a boost to the incomes of 2.4 million of the lowest paid.

The Commission understands that reducing the taper rate is hugely expensive, costing billions of pounds, and that changes to the Universal Credit system are complex. The Commission does, however, believe that that the design of Universal Credit, especially the taper rate and work allowances, should be considered over time to ensure it can best support progression incentives.

Recommendation 2.4: The Department for Work and Pensions and HM Treasury should consider how the design of Universal Credit, especially the taper rate and work allowances, can best support progression incentives.

Improving understanding of Universal Credit incentives

Universal Credit is designed to simplify the benefit system. However, it is clear from the Commission’s discussions with employers and from responses to the Call for Evidence that more can be done to help claimants and employers fully understand how employment decisions impact on Universal Credit payments. Research by the Department for Work and Pensions shows the existing system is not very well understood by claimants – the most recent Universal Credit Full Service Omnibus Survey showed that more than half of those surveyed did not understand the work allowances and earnings taper, which are intended to incentivise claimants to work.

If a significant proportion of people do not know whether they will be better off working, then more will need to be done to improve their understanding. The Commission believes that as a starting point the Department for Work and Pensions should undertake in-depth research about claimants’ understanding of the work incentives within Universal Credit, including support available for childcare costs, so that better advice and information can be given to enable more people to benefit from the improvements in the system.

This research could explore where claimants are currently getting their information about work incentives from, as it may be that the existing communication arrangements are not as well targeted as they should be. It would also be useful to understand other factors which may be preventing people from increasing the hours they work, such as caring responsibilities. The research could also seek the views of claimants about the level of incentives which they believe need to be offered to encourage them to consider increasing the hours they work. Such research could then provide an evidence base to inform future policy development about the direction of existing incentives.

The Commission has also heard from employers who have larger numbers of employees on Universal Credit that they would welcome more bespoke learning sessions on how the system works so they can better help their employees in taking career progression decisions.

Recommendation 2.3: In advance of launching its progression offer, the Department for Work and Pensions should consider a high-level communications campaign to inform people on low pay that the government is changing how it supports them; and to assure them that this support is for them regardless of their individual circumstances.

Recommendation 2.5: The Department for Work and Pensions should also commit to improving how well Universal Credit, and in particular its rules for claimants in work, are understood by employers in low pay sectors.

Recommendations

2.1. Jobcentres need to have an established, credible in-work offer for all working benefit claimants. This could include, for example, annual, high quality, progression-focused career conversations. To realise this, Jobcentres need to invest in specialist expertise in progression. This will include acting as a specialist hub for expertise on local labour markets in close partnership with local actors including employers, local authorities and skills providers, amongst others.

2.2. The Department for Work and Pensions should consider ways to incentivise claimants to reach milestones on their individual progression and learning pathways. For example, for every milestone that a claimant reaches on their individual progression and learning pathway, they could be ‘awarded’ with credits which they can put towards training or certification costs, or childcare or transport costs to allow them to reach their next milestone.

2.3. In advance of launching its progression offer, the Department for Work and Pensions should consider a high-level communications campaign to inform people on low pay that the government is changing how it supports them; and to assure them that this support is for them regardless of their individual circumstances.

2.4. The Department for Work and Pensions and HM Treasury should consider how the design of Universal Credit, especially the taper rate and work allowances, can best support progression incentives.

2.5. The Department for Work and Pensions should also commit to improving how well Universal Credit, and in particular its rules for claimants in work, are understood by employers in low pay sectors.

Chapter 3: Promoting a Culture of Lifelong Learning

A willingness to continue to learn and develop is vital to progress in the workplace. Regardless of role, or pay bracket, learning should feature at every and any stage of professional life, whether this means acquiring technical, language or digital skills, or developing confidence and leadership skills. If low-paid workers in the United Kingdom are not able and willing to develop their skills, they will find it more difficult to progress and increase their earnings.

Despite successive governments recognising the importance of developing a skilled workforce, the United Kingdom is currently ranked 13th for numeracy and 10th for literacy among the 34 OECD countries[footnote 47]. As of 2018, 6 million adults in the UK did not hold a qualification at level 2 (GCSEs)[footnote 48]. In England, research also shows that adults who have yet to attain qualifications to level 2 or above are more likely to be unemployed or have low-paid jobs[footnote 49]. Employers have also reported significant skills shortages. In 2017, 22% of vacancies in the UK were difficult to fill because of skills shortages[footnote 50]. Furthermore, the OECD’s Employment Outlook 2019 suggests that 12% of UK jobs are at high risk of automation and that those occupations at the highest risk of automation are mostly low-skilled[footnote 51].

Skills policy is devolved, to the Scottish Government, Welsh Government and the Northern Ireland Executive. Each Government is alive to the challenge of improving skills across the United Kingdom as summarised below. Skills policy is an opportunity to learn from each other, share good practice and learn from experience across the UK.

England

In January this year, the Department for Education published a White Paper on Skills for Jobs[footnote 52] for England, setting out its blueprint for ensuring that everyone has the skills they need to have good jobs, both now and in the future. The Commission welcomes this White Paper, which builds on technical education reforms, with a focus on employer needs. Local Skills Improvement Plans will bring together employers, skills providers and local stakeholders to decide on key technical skills required. The White Paper commits to increasing the provision of higher-level, high-quality technical education and training through the National Skills Fund, Institutes of Technology, T Levels and Higher Technical Qualifications.

The White Paper also sets out plans to introduce a Lifelong Loan Entitlement. This entitlement is the equivalent to 4 years’ worth of post-18 education and can be used by individuals undertaking level 4 to 6 study over their lifetime. It can also be used to support modular study. The Commission welcomes the Lifelong Loan Entitlement but notes that a loan may not be feasible for people on very tight budgets and on low pay. The Commission also acknowledges and supports the Government’s continued full funding of English and Maths qualifications (up to and including level 2), essential digital skills qualifications (up to and including level 1) and the first full level 2 and/or first full level 3 qualification for individuals aged 19 to 23. It also fully funds provision up to and including level 2 for eligible learners aged 19 and over who are unemployed or employed, or self-employed, where they are earning less than a low wage threshold (£17,374.50 gross annual salary)[footnote 53].

The Lifetime Skills Guarantee announced in September 2020 aims to help people train and retrain at any stage in their lives[footnote 54]. Adults in England who are 24 and over and do not yet have A levels, an advanced technical diploma or equivalent, can now take their first level 3 qualification for free. Adults can choose from almost 400 free courses to gain new skills that will help them access opportunities and get a better job. This means that tens of thousands of adults who have not achieved a level 3 qualification stand to benefit, which is particularly important as the Commission understands that achieving a level 3 qualification improves chances of progressing out of low pay[footnote 55].

At the same time, however, the Commission has heard that achieving the next level of formal qualifications is not always relevant or desirable for those in low pay, nor do many people feel ready to take this step. What some people need instead are technical and job-specific skills. Therefore, not all reskilling or upskilling should be focussed on attainment of formal qualifications. Appropriate targeted training for progressing in a role or in a sector should be part of this learning offer. The Commission hopes that the newly introduced Skills Bootcamps, which offer a shorter flexible programme of high quality, medium to higher level skills training for adults based on the skills in-demand by local employers and sectors, will help to fill this gap.

Scotland

The Scottish Government continues to invest in skills and education to drive economic growth and prosperity, to support high quality jobs and enable employers to gain the skilled workforce they need. In recognition of the challenges ahead, Scotland’s Future Skills Action Plan (published in 2019) is focused on improving the provision of lifelong learning and enabling people to reskill either later in life or within emerging sectors, such as the green economy. The Flexible Workforce Development Fund offers employers support to upskill and retrain their workforces to improve productivity and support economic growth. The National Transition Training Fund enables individuals to upskill or retrain where their job is at risk or to re-enter employment, supporting training in growth sectors, or those sectors most affected by the economic impact of COVID-19 and EU Exit, with a particular focus on supporting the transition to a net-zero economy. Individual Training Accounts offer unemployed people or those on low incomes the opportunity to access £200 per year to build their skills to get a job or progress in work.

Scotland’s Young Person’s Guarantee was launched in November 2020 and offers all young people between the ages of 16 and 24 the opportunity of: an apprenticeship; fair employment which includes work experience; training; a formal volunteering programme; college or university study. Scottish citizens are also exempt from paying tuition fees if they wish to study full-time at a Scottish university or college. Their fees are covered by the Student Awards Agency for Scotland.

Wales

The Welsh Government’s Economic Action Plan and Employability Plan identifies the need to promote progression to boost earnings and hours in low-paid, entry-level jobs. The Working Wales service offers free, professional employability and careers advice and guidance for anyone aged 16 and over in Wales. The service can advise on retraining support for employed people to support them in finding new or better employment, switch sectors and explore new job opportunities. They can signpost to further support such as ReAct and the Personal Learning Account Programme.

The Flexible Skills Programme supports employers to train individuals in work to improve skills levels to tackle skills shortages and improve workforce capability and productivity and is currently focussed on addressing skills gaps in advanced digital skills, as well as support for upskilling in engineering, manufacturing, creative and tourism and hospitality sectors. Apprenticeships offer a further option for individuals to progress and for employers to develop their workforce.

Skills provision in Wales has been built up from the Welsh Government’s understanding of employers’ needs through partnership working, informed by Regional Skills Partnerships, and supported by a commitment to ensure everyone aged 16 and over can access advice and support to find work, pursue self-employment or find a place in education or training. The Skills Gateway for Business also provides advice for employers on how to access funding and support to upskill their workforce. There are currently a number of ways skills and courses can be funded, including Higher Education funding.

Northern Ireland

The Northern Ireland Executive is developing a new Skills Strategy for Northern Ireland for consultation and publication in 2021. The overarching focus of the strategy is on developing a skills system which drives economic prosperity and tackles social inequality. It is founded upon three major policy objectives: addressing skills imbalances, creating a culture of lifelong learning and enhancing digital education and inclusion across society.

The Department for the Economy has allocated £6.2 million to support the provision of free, flexible, training, aimed at supporting individuals whose jobs have been directly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, to improve their skills in economically relevant areas, and thus employment opportunities. This includes an online postgraduate certificate in Software Development. In addition, they are offering a pilot scheme of Information and Communications Technology training for women returners, with a guaranteed interview from a Northern Ireland employer in the digital sector and graduate placement opportunities for recent graduates, blending training in Leadership and Management, and Digital, with an internship at a local employer.

Programmes are also offered through Northern Ireland’s Further Education Colleges. InnovateUs offers free training to small businesses with fewer than 50 employees to acquire the skills necessary to engage in innovation activities while Assured Skills is a short, demand-led, pre-employment training programme to upskill individuals and help them compete for guaranteed job vacancies in areas such as financial services, business consultancy and data analytics.

UK Shared Prosperity Fund

The commission also notes that the UK Shared Prosperity Fund (UKSPF) offers an opportunity to ensure there is provision which reflects a balance of needs between people and places across the UK in a way that is additional, complementary and does not duplicate existing UK provision. The UKSPF could be an important vehicle to ensure there is a consistent offer in place across the UK that could include equipping people with the right skills to help them overcome barriers and progress into and in work.

Learning for the low-paid: motivational and practical barriers

Those who are most likely to benefit from learning are those who are most unlikely to participate in it. Lower paid mid-career workers are the least likely to access training opportunities – with those in either intermediate or routine and manual skill-level jobs 13% and 12% less likely to have received training than those in managerial roles during 2019[footnote 56]. Dispositional barriers, such as a fear of learning or low levels of confidence, can prevent adults from taking steps towards learning, or taking more formal education[footnote 57].

Better Placed told the Commission in its response to the Call for Evidence that low-paid workers who they help:

will often seek more hours at the same pay, which is an immediate income solution. Training for potential future progression is uncertain and in many cases too much of a risk.

Better Placed Joint Committee (Lambeth, Lewisham and Southwark), In-Work Progression Commission’s Call for Evidence[footnote 58]

The Commission believes that there is also another set of challenges: practical ones such as digital access, transport and caring arrangements. Learning also needs to be flexible; available to access when it suits the individual, as far as possible, and take into account the various personal circumstances that limit time and bandwidth to pursue progression opportunities.

The Commission is pleased that the Department for Work and Pensions has already taken steps to remove barriers to learning; the new Train and Progress initiative which is aimed at increasing access to training opportunities for claimants, will see an extension to the length of time people can receive Universal Credit while undertaking work-focused study.

The Commission thinks that tailored support is needed to enable people on low pay to take up learning opportunities. This should be provided by employers, Jobcentres and National Careers Service advisers (and their equivalents in the Devolved Administrations). Everyone in work should have an individual progression and learning plan, setting out how they can progress in their existing job or area of work, or in a different one. In relation to progressing in the same workplace, large employers should ensure that plans are formulated jointly by the worker and a line manager or HR advisor. In the case of smaller organisations with fewer resources, these plans could signpost workers to other local or digital support, such as the National Careers Service in England, Careers Wales, Skills Development Scotland and Careers Service (Northern Ireland). For those in smaller organisations who are claiming Universal Credit, these plans could be developed in partnership with Work Coaches.

The Commission recognises that Wales and Scotland both already have programmes designed to support individuals with learning throughout their lives. In Wales, the Working Wales offer is intended to be the single thread that runs through an individual’s career. Advisers, working alongside Work Coaches offer personalised support and signpost to national/community provision. In Scotland, the No One Left Behind strategy also puts the individual at the centre of delivery and supports individuals to help them identify and plan their route back to, or progress in, work. The Commission would encourage the Devolved Administrations to work with employers to ensure that workers in low pay sectors are supported to continue to learn and develop and to ensure that workers are able to take advantage of new labour market opportunities.

Recommendation 3.1: People on low pay should be proactively encouraged and enabled to take up learning through a progression and learning plan. Employers, Jobcentres and National Careers Service advisers (and their equivalents in the Devolved Administrations) should work with individuals to develop and action these plans. For people on Universal Credit, these plans may, for example, be achieved through a wider use of Jobcentre claimant commitments.

Learning and older workers

Evidence suggests that people over the age of 55 are significantly less likely to participate in learning compared to younger people[footnote 59]. Considering this data in the context of people living longer and healthier lives, there is a considerable risk that older workers may find it challenging to remain in or re-enter the labour market. The Future Cohort Study discussed in Chapters 1 and 2 of this report revealed that those aged 45 and over are less likely to agree that they feel confident about applying for a new job than those under 45 (59% compared with 67%)[footnote 60].

The Department for Work and Pensions has developed the free Mid-life MOT[footnote 61], which is available across the UK. It provides online support to encourage more active career planning, including on the issue of skills and reskilling, as well as enabling productive workplace conversations. The Mid-life MOT encourages those considering a change in career to take stock across the key areas of work, wealth and wellbeing. It offers help from the National Careers Service, Skills Development Scotland and Careers Wales, NHS Better Health (England), NHS 24 (Scotland), NHS 111 (Wales), Health and Social Care Online (Northern Ireland) and Money and Pensions Service.

In February 2021, the Department for Work and Pensions held short mid-life MOT Digital Discovery Trials in 10 Local Enterprise Partnerships (England only) to test a localised and place-based approach to delivering the Mid-life MOT aimed at improving signposting and access to the Mid-life MOT and building the capability of small and medium-sized firms who find it less easy to help their staff access it.

The Commission recommends that employers of all sizes and in all sectors use this Mid-life MOT to help their older workers assess their career needs, including skills. The Department for Work and Pensions should review the MOT to ensure that it is relevant to those in low pay and is easy to use in support of progression.

Recommendation 3.2: The Department for Work and Pensions should review the Mid-life MOT to ensure it is easy to use for those in low pay and that it is used more often and more widely by employers of all sizes and in all sectors, as well as by Jobcentres, to help older workers to assess their career and skills needs.

The role of employers in changing the learning culture

There is a business case for investment in learning. Recent CIPD research found that more productive firms were more likely to train and invest to tackle skills gaps in their workforce. 75% of organisations who reported above-average productivity developed talent internally, compared with just 42% of those who report below-average productivity[footnote 62]. In addition, a report by Gallup, considering a global study of nearly 50,000 business units in 45 countries, also found that businesses that develop their staff’s strengths have been found to reduce employee turnover by up to 72%[footnote 63]. Accenture Business Case for Employability Programmes research commissioned by three English NHS trusts demonstrated that for every £1 spent on employability programmes, Trusts could recoup that £1 alongside an additional £2.50 in financial and economic benefits[footnote 64].

Some employers may be reluctant to offer learning opportunities that lead to transferable qualifications which equip an employee to apply for other jobs[footnote 65]. However, the Employer Skills Survey 2019 found that 9 in 10 (90%) employers felt that having staff attain vocational qualifications had led to better business performance and 78% had experienced improved staff retention[footnote 66]. Similarly, in a report by LinkedIn Learning, a global study showed that 94% of employees agreed that they would stay at a company longer if it invested in their career development.[footnote 67]

The Commission found further evidence for this in conversations with employers.

National Express revealed that they have employees who have built careers of 30 years or more with the company. National Express recognises that their people may want to stay with a company for decades, but most won’t want to do the same job for that whole time. The company credits their learning programme as helping to build loyalty and they now include their learning offer in their recruitment campaigns as evidence of their commitment to development. Their approach to skills development has enabled them both to retain talent and helped them recruit new talent as their people act as advocates for the company.

McDonald’s invests £43 million in learning each year, and shared their rationale for supporting staff learning and development with the Commission:

We need our people to succeed if we are going to be successful. It is because of this focus on our people that we are proud to say that many stay with us for a large part of their careers. In fact, 9 out of 10 of our restaurant managers, and one in 5 of our franchisees, started out as crew members behind the counter or in the kitchens. Additionally, one third of our executive team started their career in one of our restaurants. We are especially proud of this because it is a clear result of how we have prioritised people’s training and progression throughout their career at McDonald’s… The McDonald’s training philosophy centres on career long learning – “from the crew room to the boardroom”. Every one of our employees working for McDonald’s has the opportunity to take part in structured training, whether it’s in customer service, teamwork or financial management. Although a huge number of our employees do want to stay at the company, for those that want to change careers – we set them up by providing them with business skills that last a lifetime.

McDonald’s, In-Work Progression Commission’s Call for Evidence[footnote 68]